6 things to bear in mind when localising video games

The year is 1991. Your humble blogger sits cross-legged, resplendent in his Global Hypercolor tshirt and Reebok Pump trainers (sneakers, to my friends across the Atlantic – localisation, see?). I blow on the Bakelite-mounted copper connectors of my brand-new Zero Wing cartridge to ensure that it fires up first time, then slot it home into my Mega Drive (Genesis, to my friends across the Atlantic – localisation is fun!). Full disclosure; I never wore the aforementioned apparel, I lived in army boots, jeans and thrash band tshirts, but there’s no personal Mandela Effect as far as Sega’s paradigm-shifting 16-bit beast is concerned. That console left a mark.

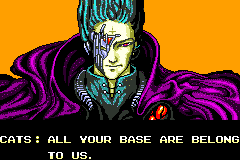

As the intro played through on my TV, my fledgling linguist brain was assaulted by the following:

As was sadly typical for the time, my initial response was one of exasperation at the prospect of yet another game story rendered unintelligible by poor translation, presumably by somebody working into their second language, which was then an all-too-common an occurrence. Fortunately, with the advent of a certain little grey box marketed by Sony, the video game industry became big business on a global level and effective localisation swiftly became a must. It’s been a learning curve and below are some of the potential pitfalls that we linguists face.

- The KISS principle

Be concise in your use of language to present key information clearly; this avoids taking up scant screen real estate which can ruin the gaming experience. The balancing act is in not prioritising conciseness over clarity.

- Correct use of register

It is essential to adhere to the rules for addressing the players in their native language; in UK English we tend to use the word “please” when issuing instructions, which may be inferred as unnecessary or even sarcastic in other cultures. In romance languages, there is the dilemma of choosing between formal and informal conjugations for “you”, each having their own inferences for the player. This should not be confused with the register applied in game dialogue, which is dependent entirely upon the characterisation, which absolutely must be taken into account. The localised cutscene exchanges between Goro Majima and Kazuma Kiryu in Ryu Ga Gotoku’s “Like a Dragon” franchise are an excellent example of how to get this right.

- Slang/swearing

Nothing dates as quickly as slang – I think back through all the “megas”, “brills” and “sorteds” that I have uttered while growing up and shake my head. An in-depth profile of the target demographic is key here. The same applies if there is any fruitier language requiring localisation – dynamic equivalence is the only way to go. Even between US English and UK English, the use of a same certain term can be classed as “suitable for all” or “PG-13”, depending on the locale.

- Quotations/idiomatic expressions

The linguists amongst you will most likely be breaking out in a cold sweat at this subheading. Literal translation is a no-no. There will be a cultural equivalent or similar expression conveying the same concept. Pragmatic equivalence is the solution; find a target language idiomatic expression that makes the same point and prompts the same reaction.

- Hypertext/Placeholders

The use of CAT tools actually makes dealing with hypertext mark-ups and placeholders a little easier, provided the translator is fully proficient in the use of such tools. The translator also needs to know how such mark-up language and tagged structuring works. Playthrough QA is always required as the CAT tool environment makes it challenging to take narrative flow into account. This brings us neatly to the main umbrella solution that can certainly contribute to overcoming the above 5 tricky areas:

- Transcreation

In video game localisation, a good translation is a reflection of how effectively the intended meaning is conveyed and how well the intended player response is elicited within their cultural context, rather than how meticulously the definition of each word is applied. It’s all about the gaming experience. Dynamic and pragmatic effect achieved through natural-sounding language are the goals here. Being a gamer, and having suffered rage-quittingly poor localisation, helps with being mindful of what not to do.

For more information on my translation, localisation and transcreation services, please visit my website: https://bufferytranslations.co.uk/services/